hurtling lovers

in these deep dark hours

hasty rain

on thirsty flowers

desperate wishes

for some stolen nights

no one knows what is wrong

or what is right

add up your sorrows

and fly them like some flags

feel the wind as

it blows them ragged

it’s more than water

in a bruised angel’s eyes

dashed on the rocks

of a lover’s lies

these fragile secrets

oh they burn us if untold

which one to wager

and which one to fold

add up your sorrows

and dry them in your eyes

memorize the flowers

as they curl up and die

we brandish our bruises

like immaculate fools

why do we cherish

the things that we lose?

why do we cherish

the things that we bruise?

why can't we cherish

the things that are true?

Saturday, 27 November 2010

Friday, 26 November 2010

Pan Am - Ending in tragedy - Brand Failure 3

In the 1980s, Pan American World Airways, or Pan Am, was one of the most famous brands of airline on the planet. For more than 60 years it had pioneered transocean and intercontinental flying.

Having begun life in 1927 with a few aircraft and a single route from Key West to Havana, Pan Am came to represent US commercial aviation policy overseas.

However, in the late 1980s the company started to struggle to achieve goals and performance began to slip.

However, in the late 1980s the company started to struggle to achieve goals and performance began to slip.

Then, in 1988, disaster struck. A Pan Am plane on route from London to New York disappeared from radar somewhere above Scotland. Later it emerged that a bomb had gone off in the cargo area, causing the aircraft to break in two.

The main body of the plane carried on for 13 miles before coming to ground in the small Scottish village of Lockerbie. The total search area spanned 845 square miles and debris turned up as far as 80 miles from Lockerbie.

In total, 270 people were killed, including 11 on the ground. One witness told television interviewers ‘the sky was actually raining fire.’

The horrific nature of the tragedy, the fact that everybody knew that the airline involved was Pan Am, and also the international nature of the story, meant that the Pan Am name was tarnished and could never recover.

Despite the company’s constant promises of commitment to increasing its airline’s security, the public was simply not willing to fly with Pan Am anymore.

Despite the company’s constant promises of commitment to increasing its airline’s security, the public was simply not willing to fly with Pan Am anymore.

After three years of flying with empty seats, in 1991 the company went bankrupt and shut down.

This all goes to show that some crises are too big to recover from. Pan Am handled the Lockerbie disaster as best as it could, but the decline in public confidence proved too much.

Having begun life in 1927 with a few aircraft and a single route from Key West to Havana, Pan Am came to represent US commercial aviation policy overseas.

However, in the late 1980s the company started to struggle to achieve goals and performance began to slip.

However, in the late 1980s the company started to struggle to achieve goals and performance began to slip.Then, in 1988, disaster struck. A Pan Am plane on route from London to New York disappeared from radar somewhere above Scotland. Later it emerged that a bomb had gone off in the cargo area, causing the aircraft to break in two.

The main body of the plane carried on for 13 miles before coming to ground in the small Scottish village of Lockerbie. The total search area spanned 845 square miles and debris turned up as far as 80 miles from Lockerbie.

In total, 270 people were killed, including 11 on the ground. One witness told television interviewers ‘the sky was actually raining fire.’

The horrific nature of the tragedy, the fact that everybody knew that the airline involved was Pan Am, and also the international nature of the story, meant that the Pan Am name was tarnished and could never recover.

Despite the company’s constant promises of commitment to increasing its airline’s security, the public was simply not willing to fly with Pan Am anymore.

Despite the company’s constant promises of commitment to increasing its airline’s security, the public was simply not willing to fly with Pan Am anymore.After three years of flying with empty seats, in 1991 the company went bankrupt and shut down.

This all goes to show that some crises are too big to recover from. Pan Am handled the Lockerbie disaster as best as it could, but the decline in public confidence proved too much.

Compulsory Voting

WHAT ARE THE ARGUMENTS FOR AND AGAINST MAKING VOTING COMPULSORY?

In many countries around the world individuals can choose to vote, or not to vote, as they see fit. In some countries (Australia, Switzerland and Singapore, for example) it is compulsory to vote in elections. The proposition in this debate must advocate some sort of punishment as an enforcement mechanism - a fine equivalent to about 100 US dollars is the norm. In some countries a no-vote box is available on the ballot paper, which can be crossed by those who do not wish to vote for any of the candidates standing.

The Argument For

In all democracies around the world voter apathy is highest among the poorest and most excluded sectors of society. Since they do not vote the political parties do not create policies for their needs, which leads to a vicious circle of increasing isolation. By making the most disenfranchised vote the major political parties are forced to take notice of them. An example of this is in the UK where the Labour party abandoned its core supporters to pursue ‘middle England’.

A high turnout is important for a proper democratic mandate and the functioning of democracy. In this sense voting is a civic duty like Jury service. Jury service is compulsory in order that the courts can function properly and is a strong precedent for making voting compulsory.

A high turnout is important for a proper democratic mandate and the functioning of democracy. In this sense voting is a civic duty like Jury service. Jury service is compulsory in order that the courts can function properly and is a strong precedent for making voting compulsory.

The right to vote in a democracy has been fought for throughout modern history. In the last century alone the soldiers of numerous wars and the suffragettes of many countries fought and died for enfranchisement. We should respect their sacrifice by voting.

People who know they will have to vote will take politics more seriously and start to take a more active role.

Compulsory voting is effective. In Australia the turnouts are as high as 98%!

Postal and proxy voting is available for those who are otherwise busy. In addition, when Internet voting becomes available in a few years everyone will be able to vote from their own home.

The Argument Against

The idea is nonsense. Political parties do try and capture the ‘working-class’ vote. The labour party shifted to the right in the UK because no-one was voting for it; the majority of the population, from across the social spectrum, no longer believed in its socialist agenda and it altered its policies to be more in line with the majority of the population. Low turnout is best cured by more education, for example, civics classes could be introduced at school. In addition, the inclusion of these ‘less-interested’ voters will increase the influence of spin as presentation becomes more important. It will further trivialise politics and bury the issues under a pile of hype.

Just as fundamental as the right to vote in a democracy is the right not to vote. Every individual should be able to choose whether or not they want to vote. Some people are just not interested in politics and they should have the right to abstain from the political process. It can also be argued that it is right that voices of those who care enough about key issues to go and vote deserve to be heard above those who do not care so strongly. Any given election will function without an 100% turnout; a much smaller turnout will suffice. The same is not true of juries which do require an 100% turnout all of the time! However, we can take a more general view by noting that even in a healthy democracy it is not surprising people should not want to do jury service because of time it takes, therefore it is made compulsory. However, in a healthy democracy people should want to vote. If they are not voting it indicates there is a fundamental problem with that democracy; forcing people to vote cannot solve such a problem. It merely causes resentment.

Just as fundamental as the right to vote in a democracy is the right not to vote. Every individual should be able to choose whether or not they want to vote. Some people are just not interested in politics and they should have the right to abstain from the political process. It can also be argued that it is right that voices of those who care enough about key issues to go and vote deserve to be heard above those who do not care so strongly. Any given election will function without an 100% turnout; a much smaller turnout will suffice. The same is not true of juries which do require an 100% turnout all of the time! However, we can take a more general view by noting that even in a healthy democracy it is not surprising people should not want to do jury service because of time it takes, therefore it is made compulsory. However, in a healthy democracy people should want to vote. If they are not voting it indicates there is a fundamental problem with that democracy; forcing people to vote cannot solve such a problem. It merely causes resentment.

The failure to vote is a powerful statement, since it decreases turnout and that decreases a government’s mandate. By forcing those who do not want to vote to the ballot box, a government can make its mandate much larger than the people actually wish it to be. Those who fought for democracy fought for the right to vote not the compulsion to vote.

People who are forced to vote will not make a proper considered decision. At best they will vote randomly which disrupts the proper course of voting. At worst they will vote for extreme parties as happened in Australia recently.

The idea is not feasible. If a large proportion of the population decided not to vote it would impossible to make every non-voter pay the fine. If just 10% of the UK voters failed to do so the government would have to chase up about 4 million fines. Even if they sent demand letters to all these people, they could not take all those who refused to pay to court. Ironically, this measure hurts most those who the proposition are trying to enfranchise because they are least able to pay.

Many people don’t vote because they are busy and cannot take the time off. Making voting compulsory will not get these people to the ballot box if they are actually unable to do so.

In many countries around the world individuals can choose to vote, or not to vote, as they see fit. In some countries (Australia, Switzerland and Singapore, for example) it is compulsory to vote in elections. The proposition in this debate must advocate some sort of punishment as an enforcement mechanism - a fine equivalent to about 100 US dollars is the norm. In some countries a no-vote box is available on the ballot paper, which can be crossed by those who do not wish to vote for any of the candidates standing.

The Argument For

In all democracies around the world voter apathy is highest among the poorest and most excluded sectors of society. Since they do not vote the political parties do not create policies for their needs, which leads to a vicious circle of increasing isolation. By making the most disenfranchised vote the major political parties are forced to take notice of them. An example of this is in the UK where the Labour party abandoned its core supporters to pursue ‘middle England’.

A high turnout is important for a proper democratic mandate and the functioning of democracy. In this sense voting is a civic duty like Jury service. Jury service is compulsory in order that the courts can function properly and is a strong precedent for making voting compulsory.

A high turnout is important for a proper democratic mandate and the functioning of democracy. In this sense voting is a civic duty like Jury service. Jury service is compulsory in order that the courts can function properly and is a strong precedent for making voting compulsory.The right to vote in a democracy has been fought for throughout modern history. In the last century alone the soldiers of numerous wars and the suffragettes of many countries fought and died for enfranchisement. We should respect their sacrifice by voting.

People who know they will have to vote will take politics more seriously and start to take a more active role.

Compulsory voting is effective. In Australia the turnouts are as high as 98%!

Postal and proxy voting is available for those who are otherwise busy. In addition, when Internet voting becomes available in a few years everyone will be able to vote from their own home.

The Argument Against

The idea is nonsense. Political parties do try and capture the ‘working-class’ vote. The labour party shifted to the right in the UK because no-one was voting for it; the majority of the population, from across the social spectrum, no longer believed in its socialist agenda and it altered its policies to be more in line with the majority of the population. Low turnout is best cured by more education, for example, civics classes could be introduced at school. In addition, the inclusion of these ‘less-interested’ voters will increase the influence of spin as presentation becomes more important. It will further trivialise politics and bury the issues under a pile of hype.

Just as fundamental as the right to vote in a democracy is the right not to vote. Every individual should be able to choose whether or not they want to vote. Some people are just not interested in politics and they should have the right to abstain from the political process. It can also be argued that it is right that voices of those who care enough about key issues to go and vote deserve to be heard above those who do not care so strongly. Any given election will function without an 100% turnout; a much smaller turnout will suffice. The same is not true of juries which do require an 100% turnout all of the time! However, we can take a more general view by noting that even in a healthy democracy it is not surprising people should not want to do jury service because of time it takes, therefore it is made compulsory. However, in a healthy democracy people should want to vote. If they are not voting it indicates there is a fundamental problem with that democracy; forcing people to vote cannot solve such a problem. It merely causes resentment.

Just as fundamental as the right to vote in a democracy is the right not to vote. Every individual should be able to choose whether or not they want to vote. Some people are just not interested in politics and they should have the right to abstain from the political process. It can also be argued that it is right that voices of those who care enough about key issues to go and vote deserve to be heard above those who do not care so strongly. Any given election will function without an 100% turnout; a much smaller turnout will suffice. The same is not true of juries which do require an 100% turnout all of the time! However, we can take a more general view by noting that even in a healthy democracy it is not surprising people should not want to do jury service because of time it takes, therefore it is made compulsory. However, in a healthy democracy people should want to vote. If they are not voting it indicates there is a fundamental problem with that democracy; forcing people to vote cannot solve such a problem. It merely causes resentment.The failure to vote is a powerful statement, since it decreases turnout and that decreases a government’s mandate. By forcing those who do not want to vote to the ballot box, a government can make its mandate much larger than the people actually wish it to be. Those who fought for democracy fought for the right to vote not the compulsion to vote.

People who are forced to vote will not make a proper considered decision. At best they will vote randomly which disrupts the proper course of voting. At worst they will vote for extreme parties as happened in Australia recently.

The idea is not feasible. If a large proportion of the population decided not to vote it would impossible to make every non-voter pay the fine. If just 10% of the UK voters failed to do so the government would have to chase up about 4 million fines. Even if they sent demand letters to all these people, they could not take all those who refused to pay to court. Ironically, this measure hurts most those who the proposition are trying to enfranchise because they are least able to pay.

Many people don’t vote because they are busy and cannot take the time off. Making voting compulsory will not get these people to the ballot box if they are actually unable to do so.

ERROR IDENTIFICATION #4

What's the wrong with each of the sentences below?

The answers are in the COMMENTS below. Be sure to try to find your own answers before looking at mine!

Don't give in too easily. Don't check the answer as soon as your brain starts hurting. Figure it out for yourself.

The answers are in the COMMENTS below. Be sure to try to find your own answers before looking at mine!

- Jane was remembered leaving the house at about 2.00.

- The children were wanted to come with me.

- It has been told that the road will be closed tomorrow for repairs.

- John was decided to chair the meeting.

- What you would like to drink?

- I asked Tony how was he getting to Brussels.

- Have not you finished your homework yet?

- Haven't you got nobody to help you?

- I've forgotten my watch. Which time do you make it?

- Who are coming to your party?

- There's no need for you to help cook the meal. Just sit down and enjoy.

- A: Tom's 50 tomorrow. B: Yes, I know it.

- I refuse you to go on the trip.

- He made me to do it.

- Did you remember buying some milk on your way home?

- If the stain doesn't come out of your shirt when you wash it, try to soak it first in bleach.

- He advised me giving up smoking.

- I heard a bottle smashing.

- I told where we should meet.

- She asked me the way how to get to the city centre.

- She debated if to tell her mother about the accident.

Don't give in too easily. Don't check the answer as soon as your brain starts hurting. Figure it out for yourself.

Branding Failures - Part 2 - Pear's Soap

Failing to hit the present taste

Pear’s Soap was not, by most accounts, a conventional brand failure. Indeed, it was one of the longest-running brands in marketing history.

The soap was named after London hairdresser Andrew Pears, who patented its transparent design in 1789. During the reign of Queen Victoria, Pear’s Soap became one of the first products in the UK to gain a coherent brand identity through intensive advertising. Indeed, the man behind Pear’s Soap’s early promotional efforts, Thomas J Barratt, has often been referred to as ‘the father of modern advertising.’

Endorsements were used to promote the brand. For instance, Sir Erasmus Wilson, President of the Royal College of Surgeons, guaranteed that Pear’s Soap possessed ‘the properties of an efficient yet mild detergent without any of the objectionable properties of ordinary soaps.’

Endorsements were used to promote the brand. For instance, Sir Erasmus Wilson, President of the Royal College of Surgeons, guaranteed that Pear’s Soap possessed ‘the properties of an efficient yet mild detergent without any of the objectionable properties of ordinary soaps.’

Barrat also helped Pear’s Soap break into the US market by getting the hugely influencial religious leader Henry Ward Beecher to equate cleanliness, and Pear’s particularly, with Godliness. Once this had been achieved Barratt bought the entire front page of the New York Herald in order to show off this incredible testimonial.

The ‘Bubbles’ campaign, featuring an illustration of a baby boy bathed in bubbles, was particularly successful and established Pear’s as a part of everyday life on both sides of the Atlantic. However, Barratt recognized the ever changing nature of marketing. ‘Tastes change, fashions change, and the advertiser has to change with them,’ the Pear’s advertising man said in a 1907 interview. ‘An idea that was effective a generation ago would fall flat, stale, and unprofitable if presented to the public today. Not that the idea of today is always better than the older idea, but it is different – it hits the present taste.’

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Pear’s remained the leading soap brand in the UK. However, towards the end of the century the market was starting to radically evolve.

Over the past 100 years, soap has reflected the development of consumer culture. Some of the earliest brand names were given to soap; it was one of the first mass-produced goods to be packaged and the subject of some of the earliest ad campaigns. Its manufacturers pioneered market research; the first TV ads were for soap; soap operas, tales of domestic melodrama, were so named because they were often sponsored by soap companies. Soap made men rich – William Hesketh Lever, the 33-year-old who built Port Sunlight [where Pear’s was produced], for one – and it is no coincidence that two of the world’s oldest and biggest multinationals, Unilever and Procter & Gamble, rose to power on the back of soap.

Recently though, a change has emerged. The mass-produced block has been abandoned for its liquid versions – shower gels, body washes and liquid soap dispensers. In pursuit of our ideal of cleanliness, the soap bar has been deemed unhygienic.

Of course, this was troubling news for the Pear’s Soap brand and, by the end of the last century, its market share of the soap market had dropped to a low of 3 per cent. Marketing fell to almost zero. Then came the fatal blow. On 22 February 2000 parent company Unilever announced it was to discontinue the Pear’s brand. The cost-saving decision was part of a broader strategy by Unilever to concentrate on 400 ‘power’ brands and to terminate the other 1,200. Other brands for the chop included Radion washing powder and Harmony hairspray.

Of course, this was troubling news for the Pear’s Soap brand and, by the end of the last century, its market share of the soap market had dropped to a low of 3 per cent. Marketing fell to almost zero. Then came the fatal blow. On 22 February 2000 parent company Unilever announced it was to discontinue the Pear’s brand. The cost-saving decision was part of a broader strategy by Unilever to concentrate on 400 ‘power’ brands and to terminate the other 1,200. Other brands for the chop included Radion washing powder and Harmony hairspray.

So why had Pear’s lost its power? Well, the shift towards liquid soaps and shower gels was certainly a factor. But Unilever held onto Dove, another soap bar brand, which still fares exceptionally well. Ultimately, Pear’s was a brand

What were the lessons learned from the Pear’s case? Well, firstly, every brand has its time. Pear’s Soap was a historical success, but the product became incompatible with contemporary trends and tastes. Secondly, advertising can help build a brand. But brands built on advertising generally need advertising to sustain them.

Pear’s Soap was not, by most accounts, a conventional brand failure. Indeed, it was one of the longest-running brands in marketing history.

The soap was named after London hairdresser Andrew Pears, who patented its transparent design in 1789. During the reign of Queen Victoria, Pear’s Soap became one of the first products in the UK to gain a coherent brand identity through intensive advertising. Indeed, the man behind Pear’s Soap’s early promotional efforts, Thomas J Barratt, has often been referred to as ‘the father of modern advertising.’

Endorsements were used to promote the brand. For instance, Sir Erasmus Wilson, President of the Royal College of Surgeons, guaranteed that Pear’s Soap possessed ‘the properties of an efficient yet mild detergent without any of the objectionable properties of ordinary soaps.’

Endorsements were used to promote the brand. For instance, Sir Erasmus Wilson, President of the Royal College of Surgeons, guaranteed that Pear’s Soap possessed ‘the properties of an efficient yet mild detergent without any of the objectionable properties of ordinary soaps.’Barrat also helped Pear’s Soap break into the US market by getting the hugely influencial religious leader Henry Ward Beecher to equate cleanliness, and Pear’s particularly, with Godliness. Once this had been achieved Barratt bought the entire front page of the New York Herald in order to show off this incredible testimonial.

The ‘Bubbles’ campaign, featuring an illustration of a baby boy bathed in bubbles, was particularly successful and established Pear’s as a part of everyday life on both sides of the Atlantic. However, Barratt recognized the ever changing nature of marketing. ‘Tastes change, fashions change, and the advertiser has to change with them,’ the Pear’s advertising man said in a 1907 interview. ‘An idea that was effective a generation ago would fall flat, stale, and unprofitable if presented to the public today. Not that the idea of today is always better than the older idea, but it is different – it hits the present taste.’

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Pear’s remained the leading soap brand in the UK. However, towards the end of the century the market was starting to radically evolve.

Over the past 100 years, soap has reflected the development of consumer culture. Some of the earliest brand names were given to soap; it was one of the first mass-produced goods to be packaged and the subject of some of the earliest ad campaigns. Its manufacturers pioneered market research; the first TV ads were for soap; soap operas, tales of domestic melodrama, were so named because they were often sponsored by soap companies. Soap made men rich – William Hesketh Lever, the 33-year-old who built Port Sunlight [where Pear’s was produced], for one – and it is no coincidence that two of the world’s oldest and biggest multinationals, Unilever and Procter & Gamble, rose to power on the back of soap.

Recently though, a change has emerged. The mass-produced block has been abandoned for its liquid versions – shower gels, body washes and liquid soap dispensers. In pursuit of our ideal of cleanliness, the soap bar has been deemed unhygienic.

Of course, this was troubling news for the Pear’s Soap brand and, by the end of the last century, its market share of the soap market had dropped to a low of 3 per cent. Marketing fell to almost zero. Then came the fatal blow. On 22 February 2000 parent company Unilever announced it was to discontinue the Pear’s brand. The cost-saving decision was part of a broader strategy by Unilever to concentrate on 400 ‘power’ brands and to terminate the other 1,200. Other brands for the chop included Radion washing powder and Harmony hairspray.

Of course, this was troubling news for the Pear’s Soap brand and, by the end of the last century, its market share of the soap market had dropped to a low of 3 per cent. Marketing fell to almost zero. Then came the fatal blow. On 22 February 2000 parent company Unilever announced it was to discontinue the Pear’s brand. The cost-saving decision was part of a broader strategy by Unilever to concentrate on 400 ‘power’ brands and to terminate the other 1,200. Other brands for the chop included Radion washing powder and Harmony hairspray.So why had Pear’s lost its power? Well, the shift towards liquid soaps and shower gels was certainly a factor. But Unilever held onto Dove, another soap bar brand, which still fares exceptionally well. Ultimately, Pear’s was a brand

What were the lessons learned from the Pear’s case? Well, firstly, every brand has its time. Pear’s Soap was a historical success, but the product became incompatible with contemporary trends and tastes. Secondly, advertising can help build a brand. But brands built on advertising generally need advertising to sustain them.

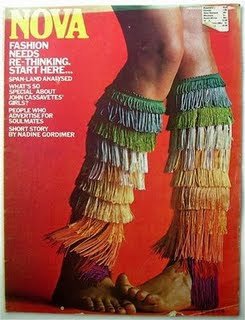

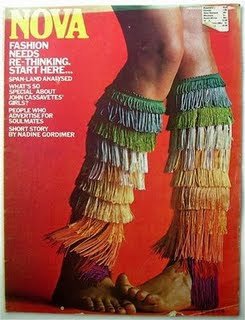

Branding Failures - Part 1 - Nova Magazine

Let sleeping brands lie

In the 1960s Nova magazine was Britain’s ‘style bible’, and had a massive impact on the fashion of the era. Alongside the fashion pages, it carried serious and often controversial articles on subjects such as feminism, homosexuality and racism. At the time, the magazine was unique, but by the 1970s other magazines started to clone the Nova concept. Nova itself soon started to look tired and fell victim to sluggish sales, and closed in 1975 after 10 years in operation – a lifetime in the magazine industry.

However, such was the impact of the magazine on its generation that IPC Magazines (which owns Marie Claire magazine) decided to relaunch the title in 2000. Second time around, the magazine was positioned as a lifestyle magazine that was as edgy and fashion-conscious as the original.

The first issue lived up to this promise. Here was a women’s magazine completely devoid of articles such as ‘10 steps to improving your relationship’, ‘How to catch the perfect man’ and ‘Celebrities and their star-signs’. According to the Guardian, the revamped Nova ‘had more humour than the failed Frank magazine, and more realistic fashion than Vogue while still being a clothes fantasy.’

Three months later though the publishers were already starting to worry that the sales figures were lower than they had anticipated. They therefore moved editor Deborah Bee, and replaced her with Jeremy Langmead, who had previously been the editor of the Independent newspaper’s Style magazine. Although some commentators questioned the decision to place a man at the helm of a magazine aimed at women, gender wasn’t the real problem. After all, Elle magazine had a male editor for many years without disastrous consequences.

Three months later though the publishers were already starting to worry that the sales figures were lower than they had anticipated. They therefore moved editor Deborah Bee, and replaced her with Jeremy Langmead, who had previously been the editor of the Independent newspaper’s Style magazine. Although some commentators questioned the decision to place a man at the helm of a magazine aimed at women, gender wasn’t the real problem. After all, Elle magazine had a male editor for many years without disastrous consequences.

Tim Brooks, the managing director of IPC, declared that the first three issues of Nova had been ‘too edgy’. But the publishers had done little to calm wary consumers by shrink-wrapping the magazine in plastic. After all, most people who purchase a new, unfamiliar magazine want to flick through it first to check that the content is relevant to them.

The new editor was quick to make changes. The novelist, India Knight, was given her own column, and more mainstream features, such as an exercise page, soon appeared. Although the magazine gathered a loyal readership, the numbers weren’t enough.

In May 2001, a year after its launch, IPC pulled the plug on Nova. ‘It is with great reluctance that we have had to make this decision,’ Tim Brooks said at the time. ‘Nova was ground-breaking in its style and delivery, but commercially has not reached its targets. IPC has an aggressive launch strategy, and an important part of this strategy is the strength to take decisive action and close unviable titles.’ IPC also said that it wanted to concentrate on the bigger-selling Marie Claire.

In May 2001, a year after its launch, IPC pulled the plug on Nova. ‘It is with great reluctance that we have had to make this decision,’ Tim Brooks said at the time. ‘Nova was ground-breaking in its style and delivery, but commercially has not reached its targets. IPC has an aggressive launch strategy, and an important part of this strategy is the strength to take decisive action and close unviable titles.’ IPC also said that it wanted to concentrate on the bigger-selling Marie Claire.

For many, the failure of Nova’s second attempt was not a surprise. ‘It was exactly like all the other magazines and failed to capture the British public’s imagination,’ said Caroline Baker, the fashion director at You magazine, and a journalist on the original Nova. ‘They should have left the old one alone, not tried to bring it back.’

Whereas the original Nova had little competition when it launched, the updated version had entered a saturated market place. 2000 had seen a whole batch of new women’s magazines enter the British market such as the pocketsized and hugely successful Glamour magazine (the first edition sold 500,000 copies). Unlike Nova, Glamour had spent masses on making sure the magazine was moulded around the market. ‘We travelled up and down the country and spoke to thousands of young women to ensure not just the right editorial, but the scale and size of the magazine,’ said Simon Kippin, Glamour’s publisher.

Commentating on Nova and other magazine closures, Nicholas Coleridge, managing director of Conde Nast Publications, said magazine closures are a fact of life for the industry. ‘It is not surprising nor horrific when magazines open and close,’ he said. ‘It’s completely predictable, and it’s been that way for hundreds of years, otherwise we would still be reading cave-man magazines.’

According to this logic the failure of Nova version two can be attributed to the natural order of magazine publishing. However, many have said that if Nova had been given more time to carve its niche, it would still be here today. One thing though, seems certain. Having already been given a second chance, it is unlikely to be allowed a third. But then again. . .

In the 1960s Nova magazine was Britain’s ‘style bible’, and had a massive impact on the fashion of the era. Alongside the fashion pages, it carried serious and often controversial articles on subjects such as feminism, homosexuality and racism. At the time, the magazine was unique, but by the 1970s other magazines started to clone the Nova concept. Nova itself soon started to look tired and fell victim to sluggish sales, and closed in 1975 after 10 years in operation – a lifetime in the magazine industry.

However, such was the impact of the magazine on its generation that IPC Magazines (which owns Marie Claire magazine) decided to relaunch the title in 2000. Second time around, the magazine was positioned as a lifestyle magazine that was as edgy and fashion-conscious as the original.

The first issue lived up to this promise. Here was a women’s magazine completely devoid of articles such as ‘10 steps to improving your relationship’, ‘How to catch the perfect man’ and ‘Celebrities and their star-signs’. According to the Guardian, the revamped Nova ‘had more humour than the failed Frank magazine, and more realistic fashion than Vogue while still being a clothes fantasy.’

Three months later though the publishers were already starting to worry that the sales figures were lower than they had anticipated. They therefore moved editor Deborah Bee, and replaced her with Jeremy Langmead, who had previously been the editor of the Independent newspaper’s Style magazine. Although some commentators questioned the decision to place a man at the helm of a magazine aimed at women, gender wasn’t the real problem. After all, Elle magazine had a male editor for many years without disastrous consequences.

Three months later though the publishers were already starting to worry that the sales figures were lower than they had anticipated. They therefore moved editor Deborah Bee, and replaced her with Jeremy Langmead, who had previously been the editor of the Independent newspaper’s Style magazine. Although some commentators questioned the decision to place a man at the helm of a magazine aimed at women, gender wasn’t the real problem. After all, Elle magazine had a male editor for many years without disastrous consequences.Tim Brooks, the managing director of IPC, declared that the first three issues of Nova had been ‘too edgy’. But the publishers had done little to calm wary consumers by shrink-wrapping the magazine in plastic. After all, most people who purchase a new, unfamiliar magazine want to flick through it first to check that the content is relevant to them.

The new editor was quick to make changes. The novelist, India Knight, was given her own column, and more mainstream features, such as an exercise page, soon appeared. Although the magazine gathered a loyal readership, the numbers weren’t enough.

In May 2001, a year after its launch, IPC pulled the plug on Nova. ‘It is with great reluctance that we have had to make this decision,’ Tim Brooks said at the time. ‘Nova was ground-breaking in its style and delivery, but commercially has not reached its targets. IPC has an aggressive launch strategy, and an important part of this strategy is the strength to take decisive action and close unviable titles.’ IPC also said that it wanted to concentrate on the bigger-selling Marie Claire.

In May 2001, a year after its launch, IPC pulled the plug on Nova. ‘It is with great reluctance that we have had to make this decision,’ Tim Brooks said at the time. ‘Nova was ground-breaking in its style and delivery, but commercially has not reached its targets. IPC has an aggressive launch strategy, and an important part of this strategy is the strength to take decisive action and close unviable titles.’ IPC also said that it wanted to concentrate on the bigger-selling Marie Claire.For many, the failure of Nova’s second attempt was not a surprise. ‘It was exactly like all the other magazines and failed to capture the British public’s imagination,’ said Caroline Baker, the fashion director at You magazine, and a journalist on the original Nova. ‘They should have left the old one alone, not tried to bring it back.’

Whereas the original Nova had little competition when it launched, the updated version had entered a saturated market place. 2000 had seen a whole batch of new women’s magazines enter the British market such as the pocketsized and hugely successful Glamour magazine (the first edition sold 500,000 copies). Unlike Nova, Glamour had spent masses on making sure the magazine was moulded around the market. ‘We travelled up and down the country and spoke to thousands of young women to ensure not just the right editorial, but the scale and size of the magazine,’ said Simon Kippin, Glamour’s publisher.

Commentating on Nova and other magazine closures, Nicholas Coleridge, managing director of Conde Nast Publications, said magazine closures are a fact of life for the industry. ‘It is not surprising nor horrific when magazines open and close,’ he said. ‘It’s completely predictable, and it’s been that way for hundreds of years, otherwise we would still be reading cave-man magazines.’

According to this logic the failure of Nova version two can be attributed to the natural order of magazine publishing. However, many have said that if Nova had been given more time to carve its niche, it would still be here today. One thing though, seems certain. Having already been given a second chance, it is unlikely to be allowed a third. But then again. . .

VOCABULARY BUILDING - Module 8

8. 1

1. lenses, 2. liable, 3. aggregate, 4. pendulum,

5. Supreme, 6. Nuclear, 7. fraternal, 8. subordinate,

9. oxygen, 10. reproduce, 11. postulated

8. 2

1. allies, 2. adhere, 3. metaphor, 4. coincided,

5. pervaded, 6. reluctant, 7. index, 8. detriment,

9. fallacy, 10. trend, 11. finite

8. 3

1. f, 2. b, 3. e, 4. k, 5. i, 6. a, 7. c, 8. d, 9. j, 10. h, 11. g

8. 4

1. evolved, 2. proclaimed, 3. cater, 4. testify, 5. drugs,

6. utilise, 7. discern, 8. territory, 9. allude, 10. launch,

11. Rebels

8. 5

1. exude, 2. allocates, 3. deprived, 4. provoked,

5. frustrated, 6. circulates, 7. league, 8. magic,

9. currency, 10. partisan

8. 6

1. sex and violence, 2. dissipates energy, 3. Peace Treaty,

4. solar power, 5. legislate against, 6. utter waste of time,

7. imperial control, 8. on the premise that, 9. invest

money, 10. give their consent

1. lenses, 2. liable, 3. aggregate, 4. pendulum,

5. Supreme, 6. Nuclear, 7. fraternal, 8. subordinate,

9. oxygen, 10. reproduce, 11. postulated

8. 2

1. allies, 2. adhere, 3. metaphor, 4. coincided,

5. pervaded, 6. reluctant, 7. index, 8. detriment,

9. fallacy, 10. trend, 11. finite

8. 3

1. f, 2. b, 3. e, 4. k, 5. i, 6. a, 7. c, 8. d, 9. j, 10. h, 11. g

8. 4

1. evolved, 2. proclaimed, 3. cater, 4. testify, 5. drugs,

6. utilise, 7. discern, 8. territory, 9. allude, 10. launch,

11. Rebels

8. 5

1. exude, 2. allocates, 3. deprived, 4. provoked,

5. frustrated, 6. circulates, 7. league, 8. magic,

9. currency, 10. partisan

8. 6

1. sex and violence, 2. dissipates energy, 3. Peace Treaty,

4. solar power, 5. legislate against, 6. utter waste of time,

7. imperial control, 8. on the premise that, 9. invest

money, 10. give their consent

Six Stages of the Essay Writing Process - 3

Stage Three: Outlining

An outline is a working plan for a piece of writing. It’s a list of all the ideas that are going to be in the piece in the order they should go. Once you’ve got the outline planned, you can stop worrying about the structure and just concentrate on getting each sentence right. In order to make an outline, you need to know basically what you’re going to say in your piece—in other words, what your theme is.

Themes

One way to find a theme is to think one up out of thin air, and then make all your ideas fit around it. Another way is to let the ideas point you to the theme—you follow your ideas, rather than direct them. As you do this, you’ll find that your ideas aren’t as haphazard as you thought. Some will turn out to be about the same thing. Some can be put into a sequence. Some might pair off into opposing groups. Out of these natural groupings, your theme will gradually emerge. This way, your theme is not just an abstract concept in a vacuum, which you need to then prop up with enough ideas to fill a few pages. Instead, your theme comes with all its supporting ideas automatically attached.

Using index cards

One of the easiest ways to let your ideas form into patterns is to separate them, so you can physically shuffle them around. Writing each idea on a separate card or slip of paper can allow you to see connections between them that you’d never see otherwise. Making an outline involves trial and error—but it only takes seconds to move cards into a new outline. If you try to start writing before the outline works properly, it could take you all week to rewrite and rewrite again. In an exam, you can’t use cards (see page 208 for another way to do it), and you’ll gradually develop a way that suits you. But doing an outline on cards—even a few times—can show you just how easy it is to rearrange your ideas.

Finding the patterns in your ideas

One way to put your ideas into order so that your theme can emerge is to use the most basic kind of order, shared by all kinds of writing:

Exactly what’s inside the compartments of Beginning, Middle and End of a piece of writing depends on whether it’s a piece of imaginative writing, an essay or some other kind of writing. It helps to remember that behind their differences, all writing shares the same three-part structure—just as all hamburgers do.

The ‘Hamburger Thing’

Making An Outline For an Essay

You’ve now got a collection of ideas that all relate in some way to your essay assignment. What you’ll do here is rearrange those ideas so they end up as an orderly sequence that will inform or persuade the reader. To do that, you’ll need to know what your theme is—the underlying argument or point of your essay. The first step towards this is to put each of your ideas on a separate card or slip of paper. That makes it much easier to find patterns in your ideas. As you look at the ideas on the cards, chances are you’ll start to notice that:

By looking at these groupings, you’ll begin to see how you can apply your ideas to the task of your assignment. Once you have a basic approach (you don’t need to know it in detail), you can begin to shape your ideas into an outline. Start with the most basic shape, using the fact that every piece of writing has a Beginning, a Middle and an End.

Beginning

Often called the introduction. Readers need all the help that writers can give them, so the introduction is where we tell them, briefly, what the essay will be about. Different essays need different kinds of introductions, but every introduction should have a ‘thesis statement’: a one-sentence statement of your basic idea. As well, an introduction may have one or more of these:

Middle

Often called the development. This is where you develop, paragraph by paragraph, the points you want to make.

A development might include:

End

Often called the conclusion. You’ve said everything you want to say, but by this time your readers are in danger of forgetting where they were going in the first place, so you remind them.

A conclusion might include:

Just sitting and looking at a list of ideas and trying to think about them in your head doesn’t usually get you anywhere. Writing is like learning to play tennis—you don’t learn tennis by thinking about it, but by trying to do it. You might have to spend a while rearranging your index cards—but it will save time and pain in the long run.

The ‘Hamburger Thing’ Again…

Different ways of organising the middle of an essay

The Middle of an essay should be arranged in an orderly way: you can’t just throw all the bits in and hope for the best. What that ‘orderly way’ is, depends on your assignment.

One-pronged essays

Some assignments only ask about one kind of thing or one way of looking at a subject. In that case you can just put the filling into the burger in whatever orderly way seems best for the subject. One kind of arrangement might be to present the ideas from the most important to least important, or from the most distant in time to the most recent.

Two-pronged essays

Some essays want you to deal with two subjects (not just oranges, but oranges and apples) or two different points of view (for example, an assignment that asks you to ‘discuss’ by putting the case for and against something, or an assignment that asks you to ‘compare’ or ‘contrast’ different views). With these twopronged assignments, it’s easy to get into a muddle with structure. For two-pronged assignments you can organise the middle in either of the following ways (but not a combination!).

Making An Outline For an Essay: 10 steps

1. Look at the assignment again

2. What groups of ideas are here?

3. Get some index cards

4. Think about your essay’s theme

5. Pick out cards for a Beginning pile

Ask these questions about each card:

Ask yourself:

7. Pick out cards for an End pile

Ask yourself:

8. Refine your outline

Ask yourself:

9. Add to the outline

Ask yourself:

10. Not working?

IN THIS SERIES ABOUT THE ESSAY WRITING PROCESS:

Previously…

To follow…

An outline is a working plan for a piece of writing. It’s a list of all the ideas that are going to be in the piece in the order they should go. Once you’ve got the outline planned, you can stop worrying about the structure and just concentrate on getting each sentence right. In order to make an outline, you need to know basically what you’re going to say in your piece—in other words, what your theme is.

Themes

One way to find a theme is to think one up out of thin air, and then make all your ideas fit around it. Another way is to let the ideas point you to the theme—you follow your ideas, rather than direct them. As you do this, you’ll find that your ideas aren’t as haphazard as you thought. Some will turn out to be about the same thing. Some can be put into a sequence. Some might pair off into opposing groups. Out of these natural groupings, your theme will gradually emerge. This way, your theme is not just an abstract concept in a vacuum, which you need to then prop up with enough ideas to fill a few pages. Instead, your theme comes with all its supporting ideas automatically attached.

Using index cards

One of the easiest ways to let your ideas form into patterns is to separate them, so you can physically shuffle them around. Writing each idea on a separate card or slip of paper can allow you to see connections between them that you’d never see otherwise. Making an outline involves trial and error—but it only takes seconds to move cards into a new outline. If you try to start writing before the outline works properly, it could take you all week to rewrite and rewrite again. In an exam, you can’t use cards (see page 208 for another way to do it), and you’ll gradually develop a way that suits you. But doing an outline on cards—even a few times—can show you just how easy it is to rearrange your ideas.

Finding the patterns in your ideas

One way to put your ideas into order so that your theme can emerge is to use the most basic kind of order, shared by all kinds of writing:

- A Beginning—some kind of introduction, telling the reader where they are and what kind of thing they’re about to read.

- A Middle—the main bit, where you say what you’re there to say.

- An End—some kind of winding-up part that lets the reader know that this is actually the end of the piece (rather than that someone lost the last page).

Exactly what’s inside the compartments of Beginning, Middle and End of a piece of writing depends on whether it’s a piece of imaginative writing, an essay or some other kind of writing. It helps to remember that behind their differences, all writing shares the same three-part structure—just as all hamburgers do.

The ‘Hamburger Thing’

TOP BUN

Where it all starts: a beginning that

gives the reader something to bite into

FILLING

A middle that gives the reader all kinds

of different stuff

BOTTOM BUN

Finishing off the piece: something to

hold it all together

Where it all starts: a beginning that

gives the reader something to bite into

FILLING

A middle that gives the reader all kinds

of different stuff

BOTTOM BUN

Finishing off the piece: something to

hold it all together

Making An Outline For an Essay

You’ve now got a collection of ideas that all relate in some way to your essay assignment. What you’ll do here is rearrange those ideas so they end up as an orderly sequence that will inform or persuade the reader. To do that, you’ll need to know what your theme is—the underlying argument or point of your essay. The first step towards this is to put each of your ideas on a separate card or slip of paper. That makes it much easier to find patterns in your ideas. As you look at the ideas on the cards, chances are you’ll start to notice that:

- some ideas go together, saying similar things;

- some ideas contradict each other;

- some ideas can be arranged into a sequence, each idea emerging out of the one before it.

By looking at these groupings, you’ll begin to see how you can apply your ideas to the task of your assignment. Once you have a basic approach (you don’t need to know it in detail), you can begin to shape your ideas into an outline. Start with the most basic shape, using the fact that every piece of writing has a Beginning, a Middle and an End.

Beginning

Often called the introduction. Readers need all the help that writers can give them, so the introduction is where we tell them, briefly, what the essay will be about. Different essays need different kinds of introductions, but every introduction should have a ‘thesis statement’: a one-sentence statement of your basic idea. As well, an introduction may have one or more of these:

- an overview of the whole subject;

- background to the particular issue you’re going to write about;

- a definition or clarification of the main terms of the assignment;

- an outline of the different points of view that can be taken about the assignment;

- an outline of the particular point of view you plan to take in the essay.

Middle

Often called the development. This is where you develop, paragraph by paragraph, the points you want to make.

A development might include:

- information—facts, figures, dates, data;

- examples—of whatever points you’re making;

- supporting material for your points—quotes, logical cause and effect workings, putting an idea into a larger context.

End

Often called the conclusion. You’ve said everything you want to say, but by this time your readers are in danger of forgetting where they were going in the first place, so you remind them.

A conclusion might include:

- a recap of your main points, to jog the readers’ memories;

- a summing-up that points out the larger significance or meaning of the main points;

- a powerful image or quote that sums up the points you’ve been making.

Just sitting and looking at a list of ideas and trying to think about them in your head doesn’t usually get you anywhere. Writing is like learning to play tennis—you don’t learn tennis by thinking about it, but by trying to do it. You might have to spend a while rearranging your index cards—but it will save time and pain in the long run.

The ‘Hamburger Thing’ Again…

TOP BUN

Beginning (introduction): where you

tell the reader briefly how you’re

going to approach the subject

FILLING

Middle (development): where you lay

out all the points you want to make

BOTTOM BUN

End (conclusion): this ties the essay

together and relates all the bits to

each other

Beginning (introduction): where you

tell the reader briefly how you’re

going to approach the subject

FILLING

Middle (development): where you lay

out all the points you want to make

BOTTOM BUN

End (conclusion): this ties the essay

together and relates all the bits to

each other

Different ways of organising the middle of an essay

The Middle of an essay should be arranged in an orderly way: you can’t just throw all the bits in and hope for the best. What that ‘orderly way’ is, depends on your assignment.

One-pronged essays

Some assignments only ask about one kind of thing or one way of looking at a subject. In that case you can just put the filling into the burger in whatever orderly way seems best for the subject. One kind of arrangement might be to present the ideas from the most important to least important, or from the most distant in time to the most recent.

Two-pronged essays

Some essays want you to deal with two subjects (not just oranges, but oranges and apples) or two different points of view (for example, an assignment that asks you to ‘discuss’ by putting the case for and against something, or an assignment that asks you to ‘compare’ or ‘contrast’ different views). With these twopronged assignments, it’s easy to get into a muddle with structure. For two-pronged assignments you can organise the middle in either of the following ways (but not a combination!).

Making An Outline For an Essay: 10 steps

1. Look at the assignment again

- This is so you don’t stray off it.

2. What groups of ideas are here?

- If you’ve got ideas that point in different directions within the assignment, you might have to decide which to focus on.

- Or you may be able to organise the ideas into a ‘two-pronged’ essay.

3. Get some index cards

- Normal sized index cards cut in half seem to be most user-friendly for this.

- Write each idea on a separate card.

- Just a word or two will do for each (enough to remind you of what the idea is).

4. Think about your essay’s theme

- Look for ideas that go together, that contradict each other, or that form a sequence.

- From those patterns, see if a theme or argument seems to be emerging.

5. Pick out cards for a Beginning pile

Ask these questions about each card:

- Is this a general concept about the subject of the assignment?

- Does it give background information?

- Is it an opinion or theory about the subject?

- Could it be used to define or clarify the terms of the assignment? If the answer to any of these is yes, put those cards together.

Ask yourself:

- Could I use this to develop an argument or a sequence of ideas about the assignment?

- Could I use this as evidence for one point of view, or its opposite?

- Could I use this as an example?

- If the answer to any of these is yes, put those cards together in a second pile.

7. Pick out cards for an End pile

Ask yourself:

- Does this summarise my approach to the assignment?

- Could I use it to draw a general conclusion?

- Could I use it to show the overall significance of the points I’ve made, and how they relate to the assignment?

8. Refine your outline

Ask yourself:

- Can I make a ‘theme’ or ‘summary’ card?

- Are the ideas in the Middle all pointing in the same direction (a onepronged essay)? If so, arrange them in some logical order that relates to the assignment.

- Are the ideas pointing in different directions, with arguments for and against, or about two different aspects of the topic (a two-pronged essay)?

- Are the cards in the Beginning in the best order? Generally you want to state your broad approach first, then refer to basic information background (such as definitions or generally agreed on ideas).

- Are the cards at the End in the best order? (You may not have any cards for your End yet . . . read on.)

9. Add to the outline

Ask yourself:

- Have I got big gaps that are making it hard to see an overall shape?

- >>> (Solution: make temporary cards that approximately fill the gap: ‘find example’ or ‘think of counter-argument’.)

- Have I got plenty in one pile but nothing in another?

- >>> (Solution: get whichever pile you have most cards for, into order. That will help you see where you go next, and you can make new cards as you see what’s needed.)

10. Not working?

- Am I stuck because I can’t think of what my basic approach should be?

- >>> (Solution: start with the Middle cards and think of how these ideas can address the assignment. If one point seems stronger than the others, see if you can think of others that build on it.)

- Am I stuck because my ideas don’t connect to each other?

- >>> (Solution: find the strongest point—the one that best addresses the assignment. Then see how the other points might relate to it. They might give a different perspective, or a contradictory one, but if they connect in some way, you can use them to develop your response to the assignment.)

- Am I stuck because I haven’t got a Beginning or an End?

- >>> (Solution: make two temporary cards:

- on the first, write ‘This essay will show…’ and finish the sentence by summarising the information you’re going to put forward, the argument you’re going to make or the two points of view you’re going to discuss;

- on the second, write ‘This essay has shown…’ and finish the sentence by recapping the information you will have given by the end of the essay, the argument you will have made, or by comingdown in favour of one of the two points of view.)

IN THIS SERIES ABOUT THE ESSAY WRITING PROCESS:

Previously…

- Stage One: Getting Ideas

- Stage Two: Choosing Ideas

To follow…

- Step Four: Drafting

- Step Five: Revising

- Step Six: Editing

DEBATE: Should We Reject The American Way Of Life?

SHOULD WE REJECT THE AMERICAN WAY OF LIFE?

SHOULD WE REJECT THE AMERICAN WAY OF LIFE?AGREE:

Moving towards the American way of life necessarily means the slow decay of individual national cultural identities. As these valuable and historically significant cultures vanish, the world will lose cultural diversity - such as in art, music, and literature - that has so enriched humanity’s history. In a world where the borders between states are becoming increasingly symbolic, the loss of diversity between countries will also mean a loss of choice for human beings with the desire to settle in a country that suits their tastes. As America’s culture becomes universal, Americans and others lose their ability to choose, even in the context of that great patriotic American slogan: “America: love it or leave it!”

Differences in ways of life between countries can have positive economic consequences. The economic theory of comparative advantage states that efficiency is maximized when those countries that can produce goods or services at the lowest cost do so. The entire concept of comparative advantage depends on major differences between countries and their respective ways of life. Convergence to the American way of life will mean the loss of some of the distinctive differences that are fundamental to maintaining countries’ comparative advantage in the supply of particular goods and services. For example, French culture is closely tied up with the idea of “terroir” - the special qualities of the land in particular regions, and this contributes strongly to its production of speciality foods and drinks - many of which are major exports.

Differences in ways of life between countries can have positive economic consequences. The economic theory of comparative advantage states that efficiency is maximized when those countries that can produce goods or services at the lowest cost do so. The entire concept of comparative advantage depends on major differences between countries and their respective ways of life. Convergence to the American way of life will mean the loss of some of the distinctive differences that are fundamental to maintaining countries’ comparative advantage in the supply of particular goods and services. For example, French culture is closely tied up with the idea of “terroir” - the special qualities of the land in particular regions, and this contributes strongly to its production of speciality foods and drinks - many of which are major exports. The American way of life is itself unhealthy for people everywhere. Defined by a taste for salty and greasy fast foods, an overloaded work schedule, and an inactive lifestyle, the American way of life is one of the most important reasons that the American population is among the world’s most unhealthy, in terms of stress, fitness, and body weight. By soundly rejecting this unhealthy way of life in favour of more sensible and healthy routines, the world does a credit to its collective health and wellbeing.

The American way of life is naturally un-diplomatic. Lacking trust in other countries and certain of its own rightness, the United States swings between isolationism and outbursts of violence, rather than consistently engaging with the rest of the world on equal terms. This arrogant impatience has historically made it a difficult ally and an intractable foe. The American way of life is marked by a strong belief in the superiority of American institutions and values, and an intolerance of alternatives. This intolerance is what has lead the United States to boldly accept the title of “world policeman,” much to the discomfort of other nations, while at the same time refusing to be bound by international agreements (e.g. on nuclear testing, climate change or the International Criminal Court).

The American way of life should be rejected because the attitudes that define it make diplomacy difficult or impossible. America has developed its unique set of cultural institutions during its more than 200 years of nationhood. As the world’s oldest democratic republic, the United States has the advantage of having developed its culture along with its own history. Like all cultures, America’s culture is tailor-made. It addresses the particular needs - present and historic - of its home country. As such, the American way of life cannot be assumed to be transferable to other parts of the world, with different histories and realities. As experiences in Vietnam in the 1970s and Iraq in the 2000s demonstrate, attempts to spread the most basic constituent of the American way of life - democracy - often end in failure.If the desirable elements of the American way of life, such as democracy, are to be adopted by people in other parts of the world, the necessary foundation must be laid organically by the country’s own experience. That is, the country must become democratic not by adopting the American way of life, but rather by proceeding through national experiences of the sort that shifted America’s own political culture toward democracy in the late 1700s.

The American way of life should be rejected because the attitudes that define it make diplomacy difficult or impossible. America has developed its unique set of cultural institutions during its more than 200 years of nationhood. As the world’s oldest democratic republic, the United States has the advantage of having developed its culture along with its own history. Like all cultures, America’s culture is tailor-made. It addresses the particular needs - present and historic - of its home country. As such, the American way of life cannot be assumed to be transferable to other parts of the world, with different histories and realities. As experiences in Vietnam in the 1970s and Iraq in the 2000s demonstrate, attempts to spread the most basic constituent of the American way of life - democracy - often end in failure.If the desirable elements of the American way of life, such as democracy, are to be adopted by people in other parts of the world, the necessary foundation must be laid organically by the country’s own experience. That is, the country must become democratic not by adopting the American way of life, but rather by proceeding through national experiences of the sort that shifted America’s own political culture toward democracy in the late 1700s. America’s culture should be rejected because it is inferior to those of many other nations. In film, music, art, sport and many other aspects of life, the American way is childish and simplistic. Hollywood only makes movies which appeal to the lowest instincts of the mass audience, delivering violence, dazzling special effects and simplistic story lines. Popular music is loud, aggressive and unsophisticated. Sports are designed for showy spectacle and constant celebration of frequent scoring, rather than as a prolonged examination of skill and strategy. Even clothing is garish and utilitarian. Such a culture has nothing to offer the rest of the world.

DISAGREE:

No culture in the world can survive if unchanging. In order to survive, the cultures of the world have always - and must always - adapted to new conditions and realities. As America’s global authority increasingly becomes a reality, cultures will begin to slowly move towards the American way of life not as a product of force, but rather as a natural consequence of increased contact with America’s dominant culture. Some cultural institutions will be lost, others will survive, and still others will become altered in reaction to it. Resisting the evolutionary impact of the American way of life would only serve to counteract an extremely important process in the histories of the world’s cultures.

No culture in the world can survive if unchanging. In order to survive, the cultures of the world have always - and must always - adapted to new conditions and realities. As America’s global authority increasingly becomes a reality, cultures will begin to slowly move towards the American way of life not as a product of force, but rather as a natural consequence of increased contact with America’s dominant culture. Some cultural institutions will be lost, others will survive, and still others will become altered in reaction to it. Resisting the evolutionary impact of the American way of life would only serve to counteract an extremely important process in the histories of the world’s cultures.Rejecting the American way of life denies the world’s people important economic advantages, especially in terms of mobility. The more similar countries’ cultures are, the more likely one is to be able to move between them, seeking economic opportunity and advantage. Many economists believe that mobility of labour (that is, the ability of workers to move across international frontiers) is an important ingredient of economic growth. As cultures move towards the American way of life, they will be better able to make easy the free movement of people to fill specific demand for their labour or skills, because many of the most difficult barriers to movement, in particular those that deal with adjustment to new cultural surroundings, would dissolve.

The American way of life may well be unhealthy, but it is also delicious. Americans are not the only people who flock to the purveyors of freeze-dried, deep-fried, sugary, salty, and greasy foods. W The reason that so many indulge this way is that fast food, for all its faults, is tasty. If we are to accept the virtues of an individual’s choice, the American way of life must not be rejected.

The American way of life may well be unhealthy, but it is also delicious. Americans are not the only people who flock to the purveyors of freeze-dried, deep-fried, sugary, salty, and greasy foods. W The reason that so many indulge this way is that fast food, for all its faults, is tasty. If we are to accept the virtues of an individual’s choice, the American way of life must not be rejected.Sparks only ever fly between countries when their foreign policies are at odds. These potentially dangerous foreign policy differences reflect deeper differences between the cultures of the countries concerned. As countries move toward the American way of life the differences that would otherwise increase the potential for foreign policy conflict will diminish. Values will become shared, institutions will become similar, and ideas will become consistent, leading to an increase in harmony between peoples and countries. It has been said that no two countries both possessing branches of MacDonalds have ever gone to war!

As far as ways of life are concerned, the American is a pretty strong choice. The American way of life boasts an emphasis on hard work, self-sacrifice, equality, and democracy. Cultures converge toward this particular set of traits because they are uniquely desirable as a way of life. Convergence between cultures is a necessary consequence of an increasingly interconnected and globalized world. And if cultures are to converge, then the American way of life, with its admirable values and great institutions, is a strong option. In other words, when it comes to cultural evolution and diffusion, one could do a lot worse than to converge towards the American way of life.

It is a mistake to see American culture as all of a piece - there are many different aspects to US popular entertainment, including jazz, blues, indie film-making, experimental art, cutting-edge architecture, demanding literature, etc. Most Americans enjoy the diversity of cultural options available to them, and it is this, as well as the individual art forms, which the rest of the world can learn from. But at its best, all American culture is possessed of a democratic spirit and accessibility, which marks it out from the elitism of art, music, etc. in much of the rest of the world.

It is a mistake to see American culture as all of a piece - there are many different aspects to US popular entertainment, including jazz, blues, indie film-making, experimental art, cutting-edge architecture, demanding literature, etc. Most Americans enjoy the diversity of cultural options available to them, and it is this, as well as the individual art forms, which the rest of the world can learn from. But at its best, all American culture is possessed of a democratic spirit and accessibility, which marks it out from the elitism of art, music, etc. in much of the rest of the world.Friday, 19 November 2010

VOCABULARY BUILDING - Module 7

7. 1

1. cells, 2. adolescents, 3. collapsed,

4. friction, 5. commodity, 6. affiliate,

7. muscle, 8. dissolve, 9. repudiated,

10. saint, 11. aristocracy, 12. democracy,

13. invoke

7. 2

1. depressed, 2. obsolete, 3. odour, 4. refute,

5. texture, 6. pragmatic, 7. incessant,

8. scores, 9. creditors, 10. confer, 11. policy,

12. migrate, 13. configuration

7. 3

1. b, 2. g, 3. e, 4. f,

5. l, 6. c, 7. a,

8. j, 9. i, 10. k,

11. d, 12. h

7. 4

1. rhythm, 2. domestic, 3. conserve, 4. defer,

5. incentives, 6. corporate, 7. fraction, 8. horror,

9. alcohol, 10. prudence, 11. negotiate,

12. competence, 13. peasants

7. 5

1. Finance, 2. reform,

3. continent, 4. tissue,

5. stereotype, 6. astronomy,

7. neutral, 8. nutrients,

9. transact, 10. schedule,

11. degrade, 12. rectangle

7. 6

1. precipitated a crisis, 2. thermal energy,

3. salt crystals, 4. pleaded not guilty,

5. a code of ethics, 6. Sibling rivalry,

7. intermediate stages, 8. political spectrum,

9. campaign of terror, 10. colloquial language,

11. contingent upon, 12. US Congress

1. cells, 2. adolescents, 3. collapsed,

4. friction, 5. commodity, 6. affiliate,

7. muscle, 8. dissolve, 9. repudiated,

10. saint, 11. aristocracy, 12. democracy,

13. invoke

7. 2

1. depressed, 2. obsolete, 3. odour, 4. refute,

5. texture, 6. pragmatic, 7. incessant,

8. scores, 9. creditors, 10. confer, 11. policy,

12. migrate, 13. configuration

7. 3

1. b, 2. g, 3. e, 4. f,

5. l, 6. c, 7. a,

8. j, 9. i, 10. k,

11. d, 12. h

7. 4

1. rhythm, 2. domestic, 3. conserve, 4. defer,

5. incentives, 6. corporate, 7. fraction, 8. horror,

9. alcohol, 10. prudence, 11. negotiate,

12. competence, 13. peasants

7. 5

1. Finance, 2. reform,

3. continent, 4. tissue,

5. stereotype, 6. astronomy,

7. neutral, 8. nutrients,

9. transact, 10. schedule,

11. degrade, 12. rectangle

7. 6

1. precipitated a crisis, 2. thermal energy,

3. salt crystals, 4. pleaded not guilty,

5. a code of ethics, 6. Sibling rivalry,

7. intermediate stages, 8. political spectrum,

9. campaign of terror, 10. colloquial language,

11. contingent upon, 12. US Congress

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)