One of the occupational diseases of writers is putting off the dreaded moment of actually starting to write. It’s natural to want to get it right first time, but that’s a big ask, so naturally you put it off some more. However, unless you’re sitting for an exam, you can do as many drafts as you need to get it right. (Some of us do quite a number: my last novel was up to draft 24 when I gave it to the publishers.) First drafts are the ones writers burn so no one can ever know how bad they were.

Only a first draft

Redrafting can seem like a chore, but you could also see it as a freedom. It means that this first draft can be as rough and ‘wrong’ as you like. It can also be (within reason) any length. In Step Five you’ll add or cut as you need to, to make it the right length, so you don’t need to worry about length at the moment. Writing is hard if you’re thinking, ‘Now I am writing my piece.’ That’s enough to give anyone the cold horrors. It’s a lot easier if you think, ‘Now I am writing a first draft of paragraph one. Now I am writing a first draft of paragraph two.’ Anything you can do to make a first draft not feel like the final draft will help. Writing by hand might make it easier to write those first, foolish sentences. Promising yourself that you’re not going to show this draft to a single living soul can help, too. But the very best trick I know to get going with a first draft is this: Don’t start at the beginning.

The GOS factor

The reason for this is the GOS factor. This is the knowledge that our piece has to have a Great Opening Sentence—one that will grip the reader from the very first moment. Probably the hardest sentence in any piece of writing is the first one (the next hardest is the GFS—the final one). Starting with the hardest sentence—the one with the biggest expectations riding on it—is enough to give you writer’s block before you’ve written a word. Years of my life were wasted staring at pieces of paper, trying to think of a GOS. These days, instead of agonising about that GOS, I just jot down a one-line summary to start with. I don’t even think about the GOS until I’ve written the whole piece. In Step Five (page 139) there’s some information about how you might write a GOS—but you don’t need it yet. No matter where you start and whatever the piece is about, you need to decide how the piece should be written—the best style for its purposes. Let’s take a minute to look into this idea of style.

About style

Style is a loose sort of concept that’s about how something is written rather than what is written. Choosing the best style for your piece is like deciding what to wear. You probably wouldn’t go to the school formal in your trackies and trainers, and it’s not likely you’d go to the gym in your silk and satin. In the same way, you wouldn’t use the same language for every situation. It all depends on what the piece of writing is for.

Choosing an appropriate style

For an essay, you’re trying to persuade or inform your reader. Therefore, you’ll want to choose a style that makes it as persuasive or informative as possible. You want to sound as if you know what you’re talking about, and that you have a considered, logical view of the assignment rather than an emotional response. Even for an essay in which you’re taking sides and putting forward an argument, you’ll be basing it on logic, not emotion.

This sense of your authority is best achieved by a fairly formal and impersonal style. You would probably choose:

- reasonably formal words (not pompous ones, though);

- no slang or colloquial words;

- no highly emotional or prejudiced language;

- third-person or passive voice (no ‘I’);

- sentences that are grammatically correct and not overly simple (but not overly tangled, either).

In a first draft, aim for these features if you can, but don’t get paralysed by them. It’s better to go back and fix them up later (Step Six shows you how) than not to be able to write a first draft at all because you’re too worried about getting it perfect.

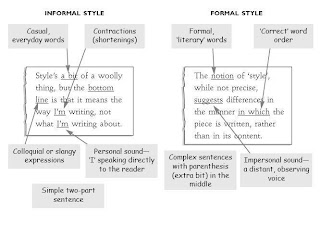

You can see from this that style boils down to three factors: word choice, voice and sentence structure. We’ll look at each of those one by one.

Choice of words

English is well-supplied with synonyms—different words that mean the same thing. They may mean the same, but you’d choose different ones for different purposes.

- The average kitchen contains quite a few cockroaches.

- The average kitchen contains heaps of cockroaches.

- The average kitchen contains numerous cockroaches.

If you were aiming to be convincing, factual and authoritative, you’d probably use ‘numerous’. If you were aiming to be chatty and friendly, you might choose ‘heaps’. If you were aiming for somewhere in between, you might use ‘quite a few’. Whichever one you choose is a matter of judging which one will serve your purposes best. That means thinking about the purpose of your piece and who will be reading it.

Voice

Listen to the following sentences. Who’s speaking in each one?

- I hate all kinds of bugs.

This sounds personal and close up, like a person talking directly to you. It’s called the first person narrator because an ‘I’ is speaking.

- You (reader) hate all kinds of bugs.

This narrator is telling you about yourself. This is the second person because the narrator is speaking to a second person, ‘you’. Sometimes the ‘you’ is not actually said, but it’s there in the background, and then it sounds as if the ‘you’ is being given an order. For example, ‘Sit down’—the ‘you’ is there but not actually said. This is called the imperative (meaning ‘what you must do’).

- He [or she] hates all kinds of bugs.

This narrator is talking about other people. It’s a sort of ‘onlooker’. This is the third person (it’s talking about things happening to a third person—a ‘he’ or a ‘she’).

- One hates all kinds of bugs.

This is when you’re talking about yourself, but in a disguised way—you’re speaking about yourself as if you’re a third person— you want to stay hidden behind a third person’s mask.

This can also be used to show that you’re speaking about people in general—to give the idea that it’s a universal truth—for example, ‘To make an omelette, one must break eggs.’

Sometimes we use ‘you’ as a more informal version of this ‘universal’ narrator, so it doesn’t sound quite so pompous—for example, ‘To make an omelette, you must break eggs.’

- Bugs are hated.

This sentence doesn’t tell us who hates bugs; someone does but the narrator has not told us. The narrator has rearranged the words so that bugs are the subject and focus of attention in the sentence. This is called the passive voice. Computer grammar checks seem to hate the passive voice, but it has its uses. It has a certain authority. It also allows the writer to hide information from the reader—in the example above, we aren’t told who hates bugs.

You can see from these examples that the choice you make will have a big effect on the way readers respond.

- If you want your readers to be charmed, to feel relaxed, to like you, you’d probably use the personal, chatty, first-person ‘I’ narrator. You might use the personal voice in a letter or for a piece of imaginative writing, for example.

- If you want them to be convinced by you and believe what you’re saying, you’d choose a less personal narrator with more authority—the third person. You would probably use third person in an essay or a report because of its confident and objective feel.

- If you want to shift the emphasis of the sentence away from the person acting, or to the action itself, you might use the passive voice. For example, in a scientific report you might say, ‘A test tube was taken’ or ‘Four families were interviewed’.

Sentence structure or syntax

Syntax just means the way you put your words together to make sentences. The simplest kind of sentence has a grammatical subject, a verb and an object: ‘I (subject) hate (verb) bugs (object).’ This arrangement can be varied. Sometimes you want to do something more elaborate like adding clauses and phrases, or changing the usual order of words. My house is full of bugs, which I hate. Bugs! I hate them. I hate bugs, although my house is full of them. Although my house is full of bugs, I hate them; however ants are different—I find them rather cute. at the

How to decide on the best style for your piece

Okay—so you can make a piece sound different depending on what style you choose. But how do you know what style is right for a particular piece of writing? The answer is to go back and look again at what your piece of writing is trying to do.

If a piece of writing is mainly setting out to entertain, you need to ask what style will be most entertaining for this particular piece.

If a piece of writing is setting out to persuade, you need to ask what style will be most persuasive.

If you’re setting out to inform, you need to ask what style will be best to convey information.

So, work out what your piece of writing is trying to do, then choose the best style for that purpose and write in it.

What if I can only think of one style?

Writing in different styles for different purposes assumes that you can choose between several ways of saying something. It assumes, for example, that you can think of another word for ‘heaps’ if you’re writing an essay. But maybe you can’t think of another way to say it.

One solution is to go to a thesaurus and try to find a similar word. This is okay in theory but the thesaurus won’t tell you whether the word you find is going to fit with the tone of your piece. It doesn’t know what kind of piece you’re writing.

A different way is to use the actor all of us have inside ourselves. Try this: if you can only think of ‘heaps’, and you know it’s too slangy for your essay, pretend you’re a school principal or the prime minister and say your sentence in the tone of voice and words you’d imagine them using. If you can only think of ‘numerous’, but you want your piece to sound relaxed and chatty, try pretending you’re on the phone to your best friend and say the sentence in the sort of words you’d probably use to him or her.

Using your outline

As you write, you might see ways to improve or add to your outline. Change it, but make sure it’s still addressing the assignment and moving in a logical way from point to point. Don’t let yourself be drawn down paths that aren’t relevant to the assignment.

Keeping the flow going

Postpone that intimidating GOS—Great Opening Sentence. Instead, use the one-line summary of your basic idea that you put at the head of your outline in Step Three. This sentence won’t appear in the final essay—it’s probably pretty dull. You’ll think of a more interesting way to start the essay in Step Five. Plunge in and try not to stop until you’ve roughed-out the whole piece. If you can’t think of the right word, put any word you can think of that is close to what you want to convey. If you’re desperate, you can always leave a blank. If you’ve forgotten a date or a name, leave a blank and come back to it later. Get spelling and grammar right if you can—but don’t let those things stop you. Don’t go back and fix things. Rough the whole thing out now and fix the details later.

Getting stuck

The Beginning of an essay is often a hard place to start. It’s where the central issue of the essay is presented—whether it’s a body of information about a subject, or a particular argument. Sometimes it’s hard to write this before you’ve written the whole piece. If you’re finding this is the case, write the Middle first. Come back later when you can see what you’ve done and tackle the Beginning. (In “Stage Five – Revising”, next week, there’s some information about getting that GOS right, but you don’t actually need it now.)

How to end it

Ending an essay can be almost as hard as starting it. The pressure is on for that Great Final Sentence to be—well—great. Take the pressure off for now. Just draw together the points you’ve made in the best final paragraph you can. You’ll probably need more than one try before you get it exactly right—don’t spend too much time on it now. (Step Five is the time for that.)Don’t give this to a reader yet. It’s rough, and they might not be able to see past the roughness to the shape underneath. Revise it first (Step Five), otherwise you might be unnecessarily discouraged.

First Draft For an Essay: 7 steps

1. Remind yourself of the ‘essay style’

Aim to use:

- • formal, non-slangy words;

- • third person or, for certain kinds of essays, passive voice;

- • grammatically correct sentences that aren’t too simplistic.

2. Write out each card on your outline

- • Start with your one-line summary of the piece. (But remember it won’t appear like this in the final draft—this is just to give you a run-up. When you’ve written the essay out, you can come back and think of a better way to start it.)

- • The idea is to expand each card into a paragraph (or several paragraphs).

- • In general, each card should be a new paragraph (this might not be true of the Beginning and End sections).

3. Structure each paragraph

Use:

- • a topic sentence which says what the paragraph will be about;

- • a development which gives more details, in a few sentences;

- • evidence which gives examples or other supporting material.

4. Link each paragraph to the assignment

Ask yourself:

- • How does this help to address the assignment I’ve been given?

- • How can I show that it addresses the assignment?

- • How can I connect this paragraph to the one before?

5. What if you can’t think of how to expand on a card?

Ask yourself:

- • Should this idea be in the essay after all?

- • Do I need to find out some more information? If so, more research might give you what you need.

- • Does this point need some support or proof? If so, go and look for some. If you can’t find anything, consider whether you should still include that point.

6. What if you get stuck?

Ask yourself:

- • Am I feeling anxious because this doesn’t sound like an essay?

- >>> (Solution: it’s not an essay yet. It’s only a first draft. Give it time.)

- • Am I having trouble thinking of the right word or right spelling?

- >>> (Solution: for the moment, just find the best approximation you can. Fix it up later.)

- • Am I stuck because I’ve forgotten a date or name or technical term?

- >>> (Solution: leave a blank and look it up when you’ve finished writing this draft.)

- • Am I stuck because my sentence has become long and tangled up in itself?

- >>> (Solution: cut the sentence up into several short, simpler ones.)

- • Do I keep going back and re-reading what I’ve done?

- >>> (Solution: just press ahead and get it all down before you go back.)

- • Is there another card further down the outline that would be easier to write about?

- >>> (Solution: leapfrog down to that card. Start the writing for it on a new page, though, and don’t forget to go back later and fill in the gap.)

- • Do I keep losing sight of how each idea is relevant?

- >>> (Solution: use key words from the assignment in each topic sentence.)

7. What if the essay changes direction?

- This is common, so don’t panic—although a well-planned outline help prevent it.

- Once you can see the new direction, stop writing and go back assignment. Would this new direction be a better way to the assignment after all?

- If you think so, go back to the index cards. Add new ones for ideas, cut out any that no longer fit, and rearrange the rest need to.

- Resume writing using the new outline and remind yourself more time outlining the next time you write an essay.

IN THIS SERIES ABOUT THE ESSAY WRITING PROCESS:

Previously… Stage One: Getting Ideas > Stage Two: Choosing Ideas > Step Three: Outling

To follow… Step Five: Revising > Step Six: Editing

Drafting has many steps. But, in my opinion, the main idea in this step is to connect with the other paragraphs. It's quite easy and quite difficult.

ReplyDelete